[ad_1]

Oakland librarian Emily Odza lives not far from the Oakland Public Library’s Eastmont Branch where she works. The neighborhood where the library is located, inside the defunct Eastmont Mall (now Eastmont Town Center), holds a special place in her heart. Odza’s mother, who used to live nearby, would shop at the mall during its heyday in the late 1960s when it first opened.

Learning about the neighborhood’s history and that of the city as a whole, said Odza, has long been a favorite pastime.

“I’ve always been wandering around Oakland looking for signs of the Oakland that used to be. It’s kind of a treasure hunt,” she said. “Finding things that remind you of the old times or indicate some history.”

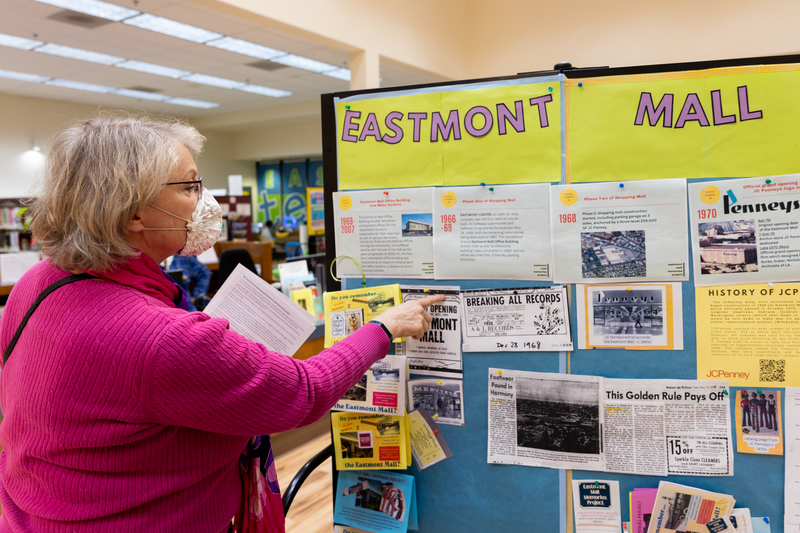

Odza’s curiosity about Oakland’s history, coupled with her work at the library, is what led to the creation of the Eastmont Mall Memories Project, an ongoing exhibit at the Eastmont Branch featuring a “community bulletin board” with photographs, newspaper clippings, written accounts, and remembrances shared by residents.

Odza said the idea was inspired by hearing from elder visitors to the Eastmont Branch who often look around in awe at how much the building, built in the 1910s, has changed over the decades.

She realized she wasn’t the only one with a fascination for Oakland history and a deep personal connection to the area. There are many locals with lived experiences and stories to share. Her only regret in starting the history project is that she didn’t begin sooner.

“I lost a lot of time and opportunities because of all those years before that we didn’t collect all those stories,” she said. “The old-timers are getting older and not coming here as often anymore.”

One of those Eastmont “old-timers” is 89-year-old David Underwood, who graduated from Oakland Tech in 1952 before joining the Air Force. During his time in the service, Underwood worked as an aircraft radio and electronics technician. When he returned to the Bay Area in 1957, he landed a job as an electrician at the Chevrolet auto plant where Eastmont Town Center is now.

When the factory was established in 1916, it was the first Chevrolet plant in Northern California. While most of its nearly five decades of operation were spent producing cars, the factory transitioned to solely manufacturing munitions and weapons during World War II. When the war ended, automotive production resumed and included Tri-Five vehicles, which are still popular among classic car enthusiasts.

“I had to get out of there,” he said of working at the factory. At the time, the auto plant was producing the Chevrolet Corvair, a compact car known for being notoriously unsafe. Besides the design flaws in the cars, Underwood said the auto plant itself “was a miserable place to work” due to unsafe conditions. He quit and moved to Southern California in 1965.

Although his time at the factory was short-lived, Underwood does have fond memories of what the Eastmont neighborhood looked like. “At that time, the neighborhood was pretty nice,” he said. “It was really what we call middle class now.”

When the auto plant was operational, the Eastmont area had a variety of movie theaters and mom-and-pop shops, including clothing and shoe stores and antique shops. Families with union jobs and other blue-collar occupations lived in the neighborhoods around the automotive factory.

In the summer of 1963, Chevrolet moved to Fremont and shuttered its Oakland location. While several options were floated as to what to do with the land—including opening a new Oakland Unified School District school—it was sold in 1964 to Community Redevelopment Corporation and transformed from an abandoned auto plant into the Eastmont Shopping Center, which later came to be known as Eastmont Mall.

As new chain stores like Mervyn’s, JC Penney, Safeway, and others opened up in the mid-1960s, the smaller mom-and-pop businesses around the neighborhood struggled to compete and began shutting down.

Meanwhile, neighbors and other Oakland residents flocked to the newly opened mall to see what it was all about. Chuck Johnson’s recollections of Eastmont Mall date back to his time watching movies at the cinema it once housed.

“I knew the routes to Eastmont Mall by foot,” said Johnson, who lived in the Sobrante Park neighborhood. “In my era, you could find packs of kids walking up and down the street. You felt a certain family unity in the city.”

As a teenager, Johnson and his friends were drawn to the mall by the growing Black culture inside, where many small Black-owned shops shared space with big retailers. In 1991, he landed his first job at the mall, working at Foot Locker.

“From that experience, I saw the different changes that the mall underwent from the 1980s to the 1990s,” he said of the beginning of the demise of big retailers at Eastmont Mall. As those stores began closing down, other smaller businesses would move in, often unsuccessfully. Meanwhile, he said, all of the investment and energy was going to newer suburban malls like Bayfair Mall in San Leandro, and Southland Mall in Hayward.

A place for Black culture to shine

In 1991, a Black-owned public access TV station found a home in Eastmont Mall. Soul Beat TV, founded by a different Chuck Johnson (he passed away in 2004), gained popularity among Black viewers with its shows and music videos featuring Black artists. The station also ran commercials for the smaller Black-owned retailers inside the mall and around Oakland.

The younger Chuck Johnson (no relation to Soul Beat’s founder) began working at the TV station as an intern, then camera operator, and eventually was given his own show called The Rap Show with Chuck, which aired from 1994-1996.

Soul Beat was originally broadcast from its founder’s home in Oakland. According to Johnson, the former show host, moving the station into Eastmont Mall allowed it to take a giant leap.

“By moving into Eastmont Mall, we had a chance to start creating sets and having a bigger location to develop content,” Johnson said. “It was unique because it was in the mall. We would go live, and people knew that we were at the mall and would show up trying to meet the artists or meet us [the hosts].”

Soul Beat was plagued with financial woes throughout its 25 years and was eventually forced to leave the mall in 1999, and shuttered for good in 2003. “When Chuck [Johnson] died, Soul Beat was like the Titanic. It went down with him,” Johnson said. But it was an important purveyor of Oakland culture and also helped catapult the careers of up-and-coming artists visiting the Bay, who would later become international superstars. Artists like Snoop Dogg, Jay-Z, and even Michael Jackson walked through Soul Beat’s studios.

In March 2020, longtime radio personality Rynell “Showbiz” Williams launched a Soul Beat TV Instagram page. In the years since, Johnson has taken over control of the page and the content.

Since the Instagram page launched, people who remember Soul Beat TV have expressed a desire to see its resurgence. If money weren’t an issue, Johnson said, he would embrace bringing the TV station back. “I don’t even know what Soul Beat TV would look like in 2023,” he said. “Soul Beat has impacted pretty much every sector of this city. I would love to work with people who can see the richness of the brand resurfacing,” he said.

From good times to hard times, now a social services hub

As for Eastmont Mall, Johnson wishes the area still had the energy it once did and served the same purpose—to entertain, provide retail, and a convening place for people in the surrounding neighborhoods. “It wasn’t supposed to become this big social services entity,” he said.

In the early 2000s, Eastmont Mall was rebranded as Eastmont Town Center. An Alameda County Social Services office, the Eastmont Wellness Center, and other agencies moved into the space. Not long after, an AC Transit transfer facility and an Oakland Police Department sub-station also moved in.

Eastmont Town Center was sold in 2015 to Vertical Ventures for $54.5 million and bought again by Tidewater Capital for $76.2 million in 2022. According to the East Bay Times, the latest purchase didn’t include the adjacent retail space that houses CVS, Gazalli’s Supermarket, dd’s Discounts clothing store, Taco Bell, Burger King, Autozone, and Octapharma Plasma.

Odza sees a larger narrative reflected in Eastmont Mall’s various historical phases.

“It’s integrally tied up with how Oakland has evolved,” Odza said. “Years of hard times and good times, wartime, the migration of Black people from the south here finding jobs, and the down times.”

Odza hopes to continue expanding the exhibit at the Eastmont Branch as more people who lived and worked in the neighborhood throughout the decades share their memories.

“History is not all reflected in newspaper articles,” she said. “It’s in the corners of people’s memories.”

[ad_2]

Source link