[ad_1]

Oakland residents have consistently told us that dangerous roads, traffic collisions, and crumbling infrastructure are top concerns they want the city to fix. That’s why we’ve made road safety and transit one of The Oaklandside’s core reporting beats.

A big part of this work is explaining technical terms to readers, unpacking engineering concepts and road construction methods, and describing various pieces of infrastructure that are built onto roads and paths. As with any complex field of work, transportation policy and engineering can be dominated by jargon and obscure terms.

In the course of my reporting, I’ve repeatedly had to explain these terms and concepts because the city, county, and state agencies often aren’t communicating clearly with the average person. Instead, our government agencies all too often publish technically obtuse and difficult-to-read maps, use legal language in presentations, stick to acronyms, and keep conversations at an expert level.

This is why we decided to create a glossary for roads, transportation, and transit. This list contains definitions for engineering concepts, describes the infrastructure you might see on a road, and identifies the multiple local and state government agencies that build and repair our roads.

We hope this is a useful reference for anyone trying to learn more about streets, transportation, transit, and local government.

This is a big list, but it’s not comprehensive. We plan on updating it over time as we do more reporting and learn about new stuff. If you know of something missing, or you think we could explain or define something more clearly, please let us know by emailing me at jose@oaklandside.org.

85th percentile speed

This is the speed at or below which 85% of drivers travel on a given road. Governments usually set the speed limit at this level under the assumption that the safest speed is the one that the vast majority of drivers naturally abide by. Engineers determine this speed by collecting data through surveys using various tools, including stopwatches, radar recorders, or pneumatic tubes. People driving above this speed are, in practice, driving dangerously. However, many experts, including the National Association of City Transportation Officials, say that using the 85th percentile speed to determine what is or is not safe is problematic because speeding drivers raise the average above what is truly safe. California recently passed laws allowing cities like Oakland to set speed limits below the 85th percentile speed, especially on roads near schools and senior homes.

Alameda County Transportation Commission

The Alameda County Transportation Commission, or ACTC, is a regional government body created by the state in 1971 to manage local transportation funds derived from sales taxes. The commission has 22 board members, including all of the county supervisors, two representatives from the city of Oakland, one representative from Alameda County’s 13 other cities, and reps from AC Transit and BART. ACTC handles about $200 million annually and has financially supported big road projects in Oakland, from the completion of CA-24 to the redesign and transformation of San Pablo Avenue.

Alignment

Alignment is the path a road takes over the landscape, including its climbs, twists, and turns. When engineers use the term, they’re often referring to the exact middle of the road defined by a painted line. This is important because roads with different types of alignment may lead to worse or better collision rates. For example, on a highway, tighter curves can cause more crashes, while curves may slow down drivers on a local road.

Arterial road

Commonly referred to as “arterials,” these are the biggest, widest, and most heavily used types of roads in any city. Arterials were some of the first roads built in many cities, often for horse-drawn carriages. And since new roads were often built by the county, state, or federal government, arterials are sometimes officially federal or state highways, in addition to being city streets. In Oakland, International Boulevard, Bancroft Avenue, and San Pablo Avenue are some of the streets that are considered arterial roads and state highways. Because arterials are heavily used and have often not been redesigned for modern uses where more pedestrians and cyclists are using them, they are also often the location of most fatal collisions and serious injuries.

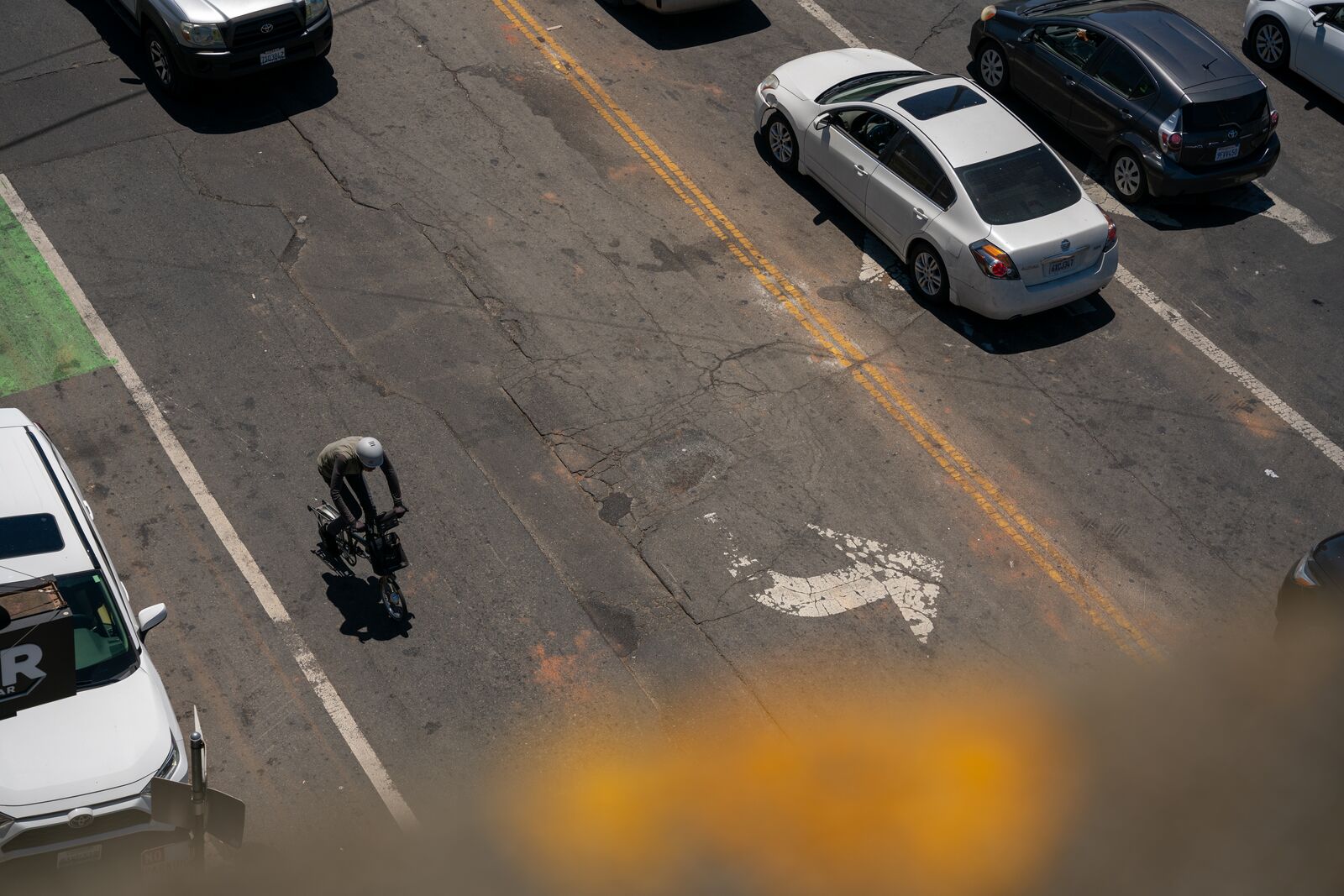

Bicycle lane

A bike lane is a part of a road where cyclists can ride. Bike lanes are sometimes identified using colorful paint and signs. They run in the same direction as cars. They’re usually on the right side of the road next to the sidewalks without parking, and between parked cars and the vehicle lane on roads with curbside parking. There are several kinds of bike lanes. Regular bike lanes, called “Class-II” lanes by Caltrans, are separated from cars on the road by a single painted line. Buffered bike lanes are separated by a painted area. And protected bike lanes are those which have some kind of physical barrier that can prevent cars and bikes from crossing over into one another’s lanes. Oakland has added many new bike lanes in recent years.

Bicyclist and Pedestrian Advisory Commission

A nine-member panel of Oakland residents who advise city transportation staff on key projects that involve paving, construction, road design, and other matters, especially as they relate to bicyclists and pedestrians. Members of the commission tend to be well-versed in transportation issues, infrastructure, and inequities in urban planning. The full BPAC meets every Thursday of the month at City Hall.

Bike box

A spot on the road at intersections for bicyclists to occupy, making them more visible to drivers. These boxes, which are often the width of the whole lane of traffic, allow cyclists wait in front of vehicles and help them make safer left turns.

Botts dotts

These small ceramic bumps are normally used to divide driving lanes on highways. In addition to being a visual marker of a lane, they also make a soft “thud” noise when a driver’s car tires roll over them. In recent years, Oakland and other cities have glued Botts dots onto the road at intersections to try to stop sideshows and other dangerous stunt driving. The idea is that if someone speedily swerves over some Botts dotts, their car’s suspension will be damaged due to the rapid jostling. Oakland has added several arrays of Botts dotts at sideshow hotspots, but the city hasn’t not said how successful they’ve been.

Bollards

Bollards are posts, normally short and cylindrical, placed on a road to protect pedestrians and bicyclists from cars. They’re also sometimes used to keep cars in specific lanes on highways. They can be permanent barriers, built into roads using heavy materials like concrete or steel, or they can be temporary and made of flimsy materials like plastic. Because they are easy to see on the road and help narrow it, bollards are often used by planners to slow down traffic. OakDOT used a lot of bollards to install the protected bike lanes on Telegraph Avenue during its pilot phase a few years ago.

Buffered bicycle lane

These are bike lanes with buffers separating them from vehicle lanes. Most buffers have some kind of high visibility pattern painted in them, such as chevrons or diagonal lines.. Bike lanes may be buffered on both sides or only on one side.

Bulb-out

Bulb-outs are sidewalk or curb extensions at a corner where one street meets another. Typically made of concrete, just like the rest of the sidewalk, bulb-outs extend into the street, making the road narrower and crosswalk lengths shorter. This makes it less likely that pedestrians will be hit when crossing. There are different types of bulb-outs used for different purposes, including bus bulbs, and pinchpoints. Bus bulbs are areas where people stand to wait for the bus. Pinchpoints are mid-block bulb extensions that narrow just one section of the road. There’s also a type called a chicane, which are curb extensions that create a zig-zag road effect to slow traffic and prevent cars from approaching a bike lane or sidewalk near a turn. Until recently, Oakland had few bulb-outs, but they are slowly being incorporated on various roads to slow down drivers. Most of the city’s bulb-outs are on corners or bus stops as bus bulbs, on streets like Telegraph Avenue with protected bike lanes.

Bus Rapid Transit

Most bus routes are on streets that don’t have any special infrastructure for buses to use. The buses travel along just like cars, pulling over to the curb to pick up and let off passengers. Bus Rapid Transit, or BRT, is a system that is meant to speed up buses along specific routes. This is accomplished by adding dedicated lanes and boarding platforms on medians in the center of the road or on bulb-outs, among other features. In Oakland, Bus Rapid Transit, or BRT, is operated by AC Transit as the “Tempo” service on Line 1T. BRT runs along International Boulevard and Telegraph Avenue.

Caltrans

The transportation department of the State of California manages all highways and freeways, and helps financially support large public transportation systems. Caltrans’ oversight in Oakland includes I-880, I-980, I-580, Highway 24, Highway 13, and all freeway offramps, bridges, and major roadways that are officially state highways like International Boulevard and San Pablo Avenue. Caltrans planners and engineers are in charge of major projects such as Vision 980, which will determine whether I-980 will be removed.

Center hardline

These are strips of hard material placed at the midway point of a road at the edge of an intersection to force drivers to stay in their lane, especially when making a left turn. Drivers turning left at an intersection will often cut across the tip of the lane occupied by cars traveling perpendicular to them. Center hardlines require the driver turning left to stay out of the lanes used by crosstraffic or else they’ll run over the barrier and damage their car. Usually, the strip is made of a combination of concrete, asphalt, or plastic and is topped with several bollards. Oakland has been adding center hardlines to the most dangerous intersections, especially in the aftermath of collisions that have led to deaths or serious injuries. For example, the city added a center hardline on 55th Street and Shattuck Avenue in North Oakland after a collision there in 2021 killed a bicyclist, and another in front of Garfield Elementary after a collision killed a young student’s mother.

Collector road

Collector roads are neither big, like arterial roads, nor small, like local roads. They’re the medium-sized streets that connect arterial roads to local roads. They often crisscross neighborhoods and are lined with businesses. Collectors usually are shorter than arterial roads, and they have slower speeds. This is why several collector roads in Oakland and the East Bay, like Shafter Avenue, are part of the area’s bike network, where bicyclists are encouraged to ride.

Collision

A crash between any combination of pedestrians, cyclists, or motor vehicles. For generations, this was called an “accident.” But in the last decade, police, transportation, and legal experts around the world have stopped using the word “accident” because it inaccurately implies a blameless and unpreventable event. Collisions always have causes, and it’s often the case that the design of a road plays a major role in how many collisions occur, where they happen, and how badly people are injured.

Corridor

Definitions can vary, but corridors are generally linear public spaces that people use to get around a city via car, bus, train, on bike, by foot, or by other means. There’s often dense housing and commercial development along corridors, which tend to be synonymous with specific large roads. Corridors include not only the street and everything on it, but also sidewalks, physical objects, facilities, and landscaping like trees, public bathrooms, and benches, and buildings. In Oakland, the biggest corridors are San Pablo Avenue, Broadway, International Boulevard, and MacArthur Boulevard.

Crosswalk

Usually located at intersections, but sometimes on other parts of a road, a crosswalk is a place where pedestrians have the right of way to get from one side of a street to another. While crosswalks are usually marked by painted stripes, markings aren’t required. Cities are increasingly adding flashing lights (see pedestrian flashing beacons) around crosswalks to highlight to drivers that they need to stop for pedestrians. Safe streets advocates have been calling for Oakland to add more crosswalks to the middle of large blocks, including in front of schools.

Cul-de-sac

A street with a dead end. In the last two decades, conversations in city planning circles have led many to conclude that cul-de-sacs are a safety and mobility problem. Cul-de-sacs can force people to drive more instead of walking or biking and they reduce access to emergency services.

Curb ramp

Otherwise known as wheelchair ramps, curb ramps are built into sidewalks to help people with mobility issues step or roll from a sidewalk onto a street and back up onto the sidewalk. Most curb ramps have tactile surfaces like ridges or raised bumps to help visually impaired people know which way to walk to cross a street or get back onto the sidewalk. Many ramps in Oakland are covered in yellow, non-slip polymer plastic composite known as “bump pads” to help make the transition even more manageable. Most cities have prioritized adding these pads at locations where many people have mobility issues, including around transit stops, hospitals, and schools. Oakland and Berkeley disability advocates were influential in the nationwide acceptance of curb ramps.

Daylighting

On many streets, it’s legal for people to park their cars close to the corners of intersections. And there’s often other visual clutter at intersections that can make it difficult for a driver to see a pedestrian trying to step out into a crosswalk in front of them, or even cross-traffic coming into the intersection. Daylighting is an engineering solution that can help improve the safety of drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians by making it easier to see other road users as they cross or pass through an intersection. It most often involves banning cars from parking within 20 feet of the corner of a street so they don’t block sightlines. Daylighting has been a part of East Coast cities’ transportation tools for many years, including in New York. California passed a law this year to make it easier for its cities to daylight intersections.

Diverter

A structure built into or placed on the road to divert traffic. Diverters can be large and solid like permanent concrete boulders or planters, such as those found at intersections in Berkeley, or they might be soft poles or signs that discourage non-local drivers from entering. Oakland doesn’t have many diverters but in early 2023, OakDOT added K-rails and signs as diverters at intersections in East Oakland to try to prevent sex workers and their customers from cruising the streets.

Dutch reach

A collision in Oakland in 2023 caused a child’s death after a person who was parked at Lake Merritt opened his car door without looking. The door swung into the unprotected bicycle lane, striking a father and his daughter who were riding a bike. The Dutch reach is a method of opening a car’s door that can prevent these kinds of collisions. To accomplish a Dutch reach, a driver uses their right hand to open their door. This forces them to swivel around, allowing them to look over their shoulder for cyclists. This is a commonly taught safety maneuver throughout the world but not as popular in the U.S. It’s known as the Dutch reach because people in the Netherlands have instituted its use in driving classes and primary school classrooms.

Easement

Sometimes a road, path, or other piece of infrastructure needs to cross over land that isn’t owned by the city that’s responsible for building and maintaining it. In order to get access to build a road across land that’s owned by someone else, a city will get an easement. This gives the city the right to continue the road through the privately owned land. Some municipalities have created easements in the East Bay to build pedestrian and bicycle routes.

E-bike

E-bikes are bicycles that are powered in part by an electric motor. There are several types of e-bikes. They include Class-I e-bikes that have pedals in addition to electrical power and travel up to 20 mph. Class II e-bikes also go up to 20 mph but don’t have pedals. These are similar to the Veo scooters you can find all over Oakland. Finally, Class-III e-bikes have pedals and can go up to 28 mph. E-bikes are allowed on all roads in Oakland where bicycles are allowed. In 2023, the East Bay Regional Park District approved Class-I e-bikes on most of the system’s trails.

Intersection crossing markings

These are painted extensions of bike lanes through intersections. In Oakland, many of these are painted as consecutive green rectangles, to highlight where cyclists are supposed to travel on the road. They show drivers and others that bicyclists have the right of way when they are traveling in these crossing lanes.

K-rails or Jersey barriers

Otherwise known as Jersey barriers, K-rails are heavy barricades usually made of cement or hard materials like rigid plastic filled with water or sand. They’re bulky and heavy enough to stop cars from smashing through them. In Oakland and elsewhere, you can see K-rails where construction is happening, creating pedestrian paths and protecting workers who are on the street from drivers. Earlier this year, OakDOT began allowing business owners to add K-rails at their storefronts to protect them from smash-and-grab robberies. The price of an individual K-rail depends on its type and size and whether they are rented or owned.

Local road

These are the smallest and least used kinds of roads, usually reserved for residential neighborhoods. Most roads in the U.S. are local roads, and they also have the lowest speed limits. Major transportation infrastructure like traffic lights are not used on local roads.

Median island

These are raised areas in a road, usually located in the middle of the street between opposite lanes of traffic, where vehicles can’t go. Sometimes they have trees or other landscaping on them, others are just concrete. Medians are often used for pedestrian crossings because they create a refuge and have been found to reduce collision rates on very wide streets. They also help prevent head-on collisions.

Metropolitan Transportation Commission

Created in 1970 by the state legislature, the MTC is responsible for helping to finance and coordinate all of the major transportation planning across the Bay Area’s nine counties. The MTC distributes money through specific grants for significant projects. For example, the MTC provided $375 million to the BART Silicon Valley extension and is working with OakDOT on the $100 million West Oakland link to create a safe bike and pedestrian road to the Bay Bridge. The MTC also helps craft our region’s housing and land use policies and plans.

OakDOT

The Oakland Department of Transportation is in charge of the city’s road planning, engineering, and management. In recent years, OakDOT has taken on other responsibilities, such as managing parking tickets and abandoned vehicle abatement. The department has only been officially in place since 2016, when it was launched by then-Mayor Libby Schaaf.

Pedestrian rapid flashing beacons

These are lights that turn on and blink rapidly to catch the attention of drivers when a pedestrian is about to cross a street. Flashing beacons can be triggered automatically or individuals can push a button to start them. They’re sometimes placed at the midway point of a long city block, especially in places where people naturally want to cross a street.

Protected bicycle lanes

These bike lanes are physically separated from the vehicle lanes by a barrier. In Oakland, most protected bike lanes are separated by bollards, cement bus bulbs, heavy planters, or rows of parked cars. In Oakland, there are protected bike lanes on Telegraph Avenue, around Lake Merritt, and soon on Fruitvale Avenue.

Raised crosswalks

These are crosswalks that are built on top of a large bump across a road. In addition to acting like a speed bump to slow cars down, they also make it easier for drivers to see pedestrians when they’re crossing the street. Raised crosswalks were added to West Street in Oakland in 2022r. Adding raised crosswalks through streets usually occurs during repaving treatments and redesigns. The US Transportation Department says that raised crosswalks can reduce collisions by up to 45%.

Red-light running

Under state law, it is illegal for a driver to enter an intersection when the signal light for their lane of traffic is solid red. It should go without saying that running a red light is extremely dangerous because cross traffic has a green light to pass through an intersection without slowing or stopping. Red-light running is part of Oakland’s traffic violence problem. There were 24 emergency calls in the city for fatalities caused by red-light violations from 2012 to 2022, according to a statement provided to The Oaklandside by the Oakland Police Department. In the U.S., upwards of 900 people a year die from red-light violations. Some municipalities have added cameras to intersections to catch red-light runners but research has been inconclusive about whether cameras and automated ticketing act as deterrents. Some experts believe that enforcement and ticketing is actually less effective at charging driver behavior than redesigning roads so that they’re inherently safer for pedestrians and other road users.

Road diet

Road diets are a process of reengineering and redesigning a street to reduce the amount of space cars take up, often with the goals of reducing vehicle speeds and making a street safer for bike riders and pedestrians. In Oakland, road diets often involve taking away a lane for vehicles and adding a bus-only lane or adding a bike lane. They’ve proven controversial in car-centric communities, with some people complaining that they slow traffic down too much. Road diets, however, usually lead to fewer collisions, as research has found that narrower roads do force drivers to slow down.

Roundabouts or traffic circles

These structures, usually round raised areas, are placed in the middle of intersections, preventing drivers from making left turns and forcing them to go right around the island to continue in any direction. The right of way is given to anyone in the roundabout first, forcing other drivers to wait their turn. Most roundabouts are added to roadways to slow down traffic, including collector and arterial roads used to get to and from the freeway. Oakland doesn’t have a lot of traffic circles, but they’ve been added to some intersections, especially near residential communities. For example, Rockridge now has a roundabout at Shafter Avenue and Hudson Street.

School zones

Areas around schools that the state and city have tried to make safer for students and their parents to walk, bike, and drive. Most school zones are within 500 to 1000 feet of schools and include lower speed limits and speed bumps. People who break the law in school zones can face higher fines than in other places. School zones also usually include school crossing guards, who help children walk across crosswalks before and after school. Oakland maintains a map of all the schools that have crossing guards.

Shared use paths

These are paths that cyclists and pedestrians can use to travel long distances without having to cross a lot of streets used by vehicles. In the East Bay, popular shared paths include the Ohlone Greenway, the Bay Bridge East Span Path, and the East Bay Greenway, which several agencies are currently working on to expand from Lake Merritt to Hayward.

Sharrows, or shared lane markings

This is a portmanteau of “share” and “arrow.” Sharrows are signs that look like a bike with arrows above them. They’re painted directly onto a road to communicate that bicycles and vehicles must share the road with each other. Roads with sharrows are on Class 3 Bike Routes and Class 3B Neighborhood Bike Routes, also known as Bike Boulevards. They’re almost always painted in the middle of lanes on arterial, collector, or local roads. They first came about in the 1990s in Denver, Colorado to make it clear that it was ok for cyclists to ride on busy roads and that drivers need to respect bicyclists. Some studies found cars tend to give more space to cyclists on roads with sharrows, but in recent years, city planners have realized keeping cyclists and cars on the same road without dedicated lanes or barriers may not be the safest way to plan for bike and car travel. Other studies have found sharrows can lead to worse collision outcomes by giving cyclists a false sense of security.

Sideshows

A controversial event where drivers take over city intersections with their cars as they skid in circles while performing stunts. Sideshows can last seconds or hours at a time, and they can be performed by a single individual without a crowd or by multiple people with hundreds of onlookers rallying them on. Some people have defended sideshows as an important outlet for youthful rebellion while others have noted that they often, especially in recent years, are accompanied by gun violence and rowdy behavior.

Slip lane

To make a right turn at an intersection, drivers usually need to slow down or come to a stop, check to be sure cross traffic isn’t coming at them, and then carry out the turn and proceed. A slip lane is a road design that allows drivers to use a dedicated turning lane without stopping, and sometimes without even slowing. Slip lanes are popular in areas where the city, county, or state wants to speed up car travel, such as highway on- and off-ramps. But because they prioritize vehicle speed over pedestrians and bicyclists, they’re often quite dangerous. In Oakland, safe street advocates have pointed out that the slip lane at 6th Street and Broadway has been dangerous to people walking and biking to and from Jack London Square because most drivers at the point are driving too fast and don’t pay as much attention when they make the turn.

Slow Streets

This was a COVID-19 pandemic program to try to encourage people to get outside and get exercise in their communities. Slow Streets are roads that cities close to through vehicle traffic, usually with signs placed in the roadway. This creates walkable boulevards in neighborhoods that reduce the presence of cars. In Oakland, Slow Streets were welcomed in some neighborhoods while others viewed them as annoying or misguided experiments. Oakland took down all Slow Streets last year, but the city is currently working on a revival of the program that would also function as bike boulevards.

Speeding

Speeding is traveling faster than the posted speed limit. The biggest factor in whether a collision is fatal is speeding. One-third of all collisions are due to speeding, and the higher the speed, the more likely a collision can lead to severe injuries or death. This is why municipalities nationwide have been working on reducing the speeds at which drivers travel on roads through legislation, road infrastructure, and sometimes through enforcement. In California, the battle against speeding recently led to a new law to add automated speed enforcement cameras to some of its city’s most dangerous corridors. Oakland will be adding 18 cameras over the next few years to stop people from speeding.

Speed bumps, humps, and tables

All of these are essentially vertical bumps on the road, usually made of cement, that run across the length of a road and force drivers to slow down. Humps are different in that they have a space so that cyclists can pass by faster without going over the hump. And tables are bumps that have a flat top, often 10 feet long, making them longer and bigger than regular bumps. Most bumps, humps, and tables are up to six inches high.

Traffic survey

Planners and engineers use surveys to learn how many cars pass through an intersection and how fast they are going, creating data they can use to make design decisions, like whether a road needs traffic-slowing infrastructure. Various kinds of technology are used to record this data, including radar sensors, which are low-radiation machines, or inductive loops, which are essentially cables under roads that can tell when cars drive over them.

Wayfinding

The way that people orient themselves around a physical space. Within the context of road design and traffic violence, proper wayfinding should include clear directionality and information, such as the location of specific paths such as bike boulevards. In modern city design, wayfinding has focused on adding signs that make it safer to walk and bike.

[ad_2]

Source link